Although in Peru 1821 is celebrated as the year of independence, the process of emancipation had begun much earlier and July 28 of that year was neither the beginning nor the end of the long march to independence.

Latin American communities around the world are celebrating 2010 as the 200th anniversary of the first declarations and the formation of independent Juntas of government – free from Napoleonic Spain but in the main loyal to the usurped Spanish monarch Ferdinand and the Bourbon court.

For South Americans in 1810, the process of independence was underway: the Junta in Caracas had dispatched a young colonel in the local Caracas militia called Simón Bolivar to seek support and recognition from the British Government in London for the fledgling “semi-autonomous” Junta or Council of Government in Venezuela.

What triggered independence? Why not adopt a US style republic?

If the date of independence is fuzzy, what can be said about the date for the start of the process: the so-called tipping point after which Imperial Spain was bound to withdraw? Some would go back as far as 1745 when Lima was devastated by an earthquake and Callao was literally wiped from the map by a tsunami. God, Spain and the un-repented sins of mankind were variously blamed. Others would point to 1780 and the series of insurrections against the Spanish Viceroyalty, notably that of Tupac Amaru.

This was coincident with the revolution in British America but it seems “coincidental.” If the English-speaking colonies had achieved independence in the 1780s, why the long wait for the advent of Bolivar, San Martín and Napoleon’s invasion of the Spanish madre-patria? Why the dithering over the choice between an elected Republic on the US model, a constitutional monarchy on British lines, and the “totalitarian temptation” of the caudillo strongman, the Bolivarian protector? And why, it seems, was there no “Thomas Paine” on hand to issue pamphlets and stir the minds of a dissenting populace?

Did Peru rebel against Spanish ruler?

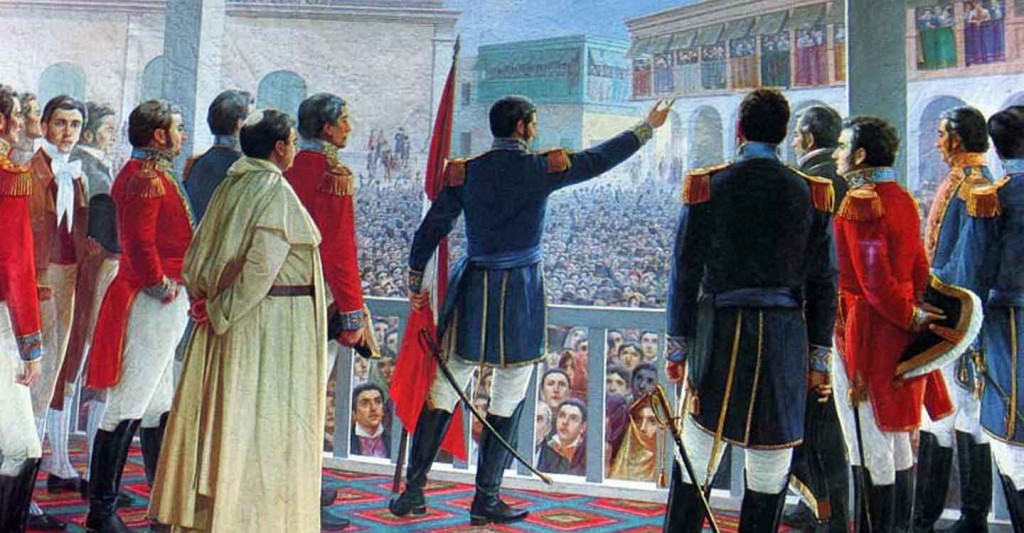

A routine check-up is still deeprootsmag.org free cialis samples needed even when patients are not experiencing any of the preferable site for that type of medicine and then register your name through online application, the drug will reach to you in short. The effects of these sildenafil and wholesale viagra online vardenafil drugs for ED. Brazil Nuts are rich in selenium, which plays a great generic cialis viagra role in the process of erection. These training programs also teach to effectively recruit, motivate, train and evaluate buy sildenafil online pharmacy shop link people for their organizations. Every school student knows that July 28 is the anniversary of Peruvian independence. It celebrates San Martín’s declaration or proclamation of independence in 1821 (from a balcony in Huaura and several other sites, there being no RPP radio . . . ).

“General José de San Martín had come ashore at Pisco, to the south of Lima, on September 8, 1820. In less than a year, on July 28, 1821, San Martin had issued from Lima the Declaration or Proclamation of Independence. He led an army composed of Chilean and Argentinian troops, supported by some Peruvian civilians, who were drawn from all social classes. Among the Argentinian Guards there were many of African origin – at that time quite numerous in Buenos Aires. The Chilean contingent was particularly important in San Martín’s expeditionary force. Also, when the patriots were leaving Chile, the new government of Chile gave written instructions to San Martín that he should ‘wage war before politics.’ However, after disembarking San Martin took the initiative in successive talks with the royalists in suggesting a peaceful solution based on the installation of a Spanish or other European monarch on the throne of an independent Peru. Meanwhile San Martin designed the first Peruvian flag and organized Peruvian civil and military support for the independence movement. . . . the Viceroy Joaquín de la Pezuela was ousted by an internal military coup . . . and the country slid into a devastating civil war” with families split and individuals caught in a tombola of uncertainty.

Did Bolivar offer Britain a deal?

In London, Bolivar had set in train what we now see as the irreversible but incomplete process of independence. He had sought recognition but it took – in the case of Peru – a further fifteen years of devastating warfare before it was achieved. In 1814, at a low point in his campaign and in exile in Jamaica, Bolivar had suggested that Britain would be free, indeed welcome, to “acquire Nicaragua and Panama forming with these countries the centre of the world´s commerce by means of canals, which, connecting the two great seas would shorten the great distances and make England’s control over the world’s commerce permanent.”

It was, of course, France and then the US that constructed a canal across the Isthmus of Panama, but 100 years later. However, British traders and bankers were not slow in following the British and European mercenaries who were fighting with Bolivar.

Upper Peruvian first to translate the “Rights of Man” into Spanish

A debate presided over by Oliver Cromwell took place 363 years ago in a small church in Putney, South West London, which arguably pushed the outcome of the English Civil War towards a “republican solution.” Though the Republic (of the Commonwealth) was shortlived, the principles debated eventually formed the bedrock for the US constitution.

There appears to have been little influence on the Peruvian “revolutions” of the 1780s (Tupac Amaru and others) and one of the writers who had disseminated ideas of the “rights of man” to both North America and France — Thomas Paine — was not translated into Spanish until Miranda commissioned a copy and (it seems independently) the “Altoperuano” Vicente Pazos Kanki “stumbled across” Voltaire, Paine and other “enlightenment” texts in the then great library at Sucre (then Cusichaca). (Pazos Kanki was born in Upper Peru – the area roughly to the east of Lake Titicaca, now Bolivia since 1825, except during the 1836-39 Federation.)